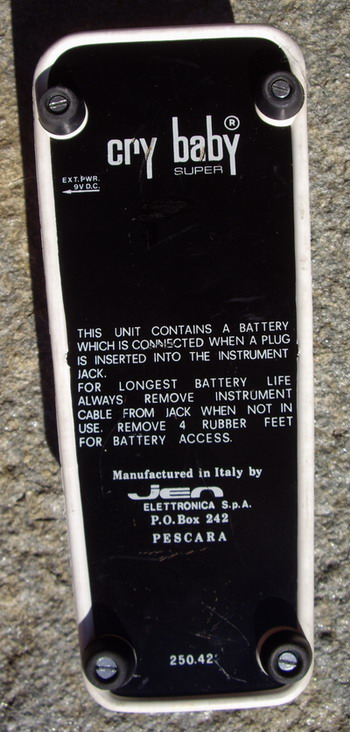

JEN CRY BABY SUPER Wha 1970

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5aAua6lDBg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Exrht8-sGr8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yUfwmx0nQC4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9atH1KFH9s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYG95DAgNlU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93dWq1bQuxM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WYPHU5xGOVc

Early versions of the Clyde McCoy featured an image of McCoy on the bottom panel, which soon gave way to only his signature. Thomas Organ then wanted the effect branded as their own for the American market, changing it to Cry Baby which was sold in parallel to the Italian Vox V846. Thomas Organ's failure to trademark the Cry Baby name soon led to the market being flooded with Cry Baby imitations from various parts of the world, including Italy, where all of the original Vox and Cry Babys were made.[3] Jen, who had been responsible for the manufacture of Thomas Organ and Vox wah pedals, also made rebranded pedals for companies such as Fender and Gretsch and under their own Jen brand. When Thomas Organ moved production completely to Sepulveda, California and Chicago, Illinois these Italian models continued to be made and are among the more collectible wah pedals today.

Beyond being crowned “Album of the Century” by Time magazine,

Marley and the Wailers’ 1977 LP Exodus is a wah-wah masterpiece thanks to Junior

Marvin and his Thomas Organ Cry Baby. Others – from Earl Hooker to Jimi Hendrix,

Frank Zappa to Sly Stone – made their mark with the pedal, but never has so much

wah been played on one album, from multi-tracked rhythm riffs to spaced-out lead

solos.

For the sessions, Marvin plugged his Fender Stratocaster into a

Roger-Mayer-tweaked Cry Baby and an Electro-Harmonix Dr. Q envelope filter, then

into two Fender Twin-Reverb amps. He layered up to six tracks of wah on top of

each other to cut the distinctive rhythms for classics like “Exodus” and “Jamming.”

The sound was part funk, part Jimi, pure reggae. “I was inspired by Jimi Hendrix

on ‘Message To Love,’ and ‘Superfly’ by Curtis Mayfield, which had a wicked wah,”

he remembers.

Electric guitarists first fiddled with their tone controls to mimic the wah-wah

sound of trumpeters such as Clyde McCoy, who waved a mute over his bellhorn to

create a human voice on his 1931 hit “Sugar Blues.” In the 1930s and ’40s,

Alvino Rey twirled the Tone knob to modulate his guitar’s timbre. Chet Atkins

did the same on the 1960 cut “Hot Toddy.”

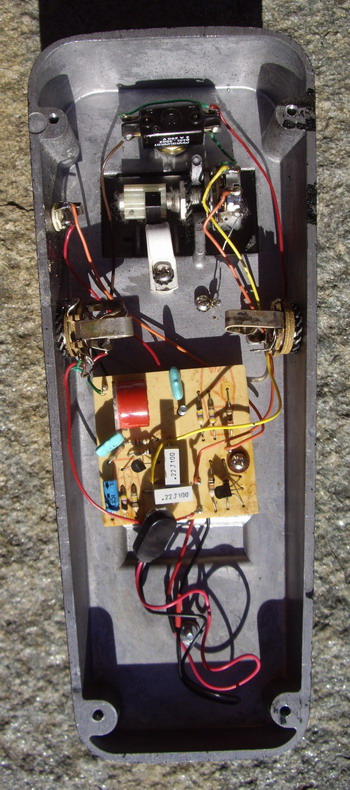

Brilliant in it its simplicity; the foot pedal drives the rotary control on the

potentiometer. This early Cry Baby features the round, brown Halo inductor,

believed by many guitarists to be the best-sounding unit.

Brilliant in it its simplicity; the foot pedal drives the rotary control on the

potentiometer. This early Cry Baby features the round, brown Halo inductor,

believed by many guitarists to be the best-sounding unit.

The wah pedal itself, however, was developed almost by accident.

In 1966, junior engineer Brad Plunkett was working at Thomas Organ Company in

Sepulveda, California. The firm had a license with musical distributor Jennings,

of England, to build and sell Vox gear in the United States. As part of this,

Thomas Organ was developing a solidstate version of the Super Beatle amp;

Plunkett was assigned to find an inexpensive replacement for the amp’s $4 Mid

Range Boost transistorized switch. He played with a 30¢ potentiometer, using it

to adjust the tone instead.

In the documentary film Cry Baby: The Pedal that Rocks the World, Plunkett

recalls, “So I went next door and asked a friend of mine, John Glenum, if he

would plug his guitar into the pile of wires and resistors and capacitors I had

on the bench. He strummed a couple of chords and I turned the knob on the

potentiometer and it went wack, wack, wack, and we looked at each other and – I

won’t tell you exactly the words we said – we said, ‘Wow, this is really great!’

“We started thinking about, ‘Well, how’s the guitarist going be able to operate

this thing? His hands are already busy.’ There was a Vox Jaguar organ sitting in

front of one of the other engineer’s benches, so I said, ‘Hey John, go steal

that volume pedal from Frank’s organ! Let’s put the pot in there.’ And pretty

soon, we were drawing a modest crowd and everybody said it sounded pretty good.

But we didn’t really know how good it was going to be.”

The up-and-down action of the foot pedal rotated the pot control, allowing the

guitarist to color the tone from treble to bass. It was a brilliantly simple

circuit, a showcase for the potential of a simple potentiometer. And Plunkett

built it into an effect that was as easy and intuitive to operate as a car’s gas

pedal.

The use of a pedal was not intuitive to Thomas Organ, however. President Joe

Benaron was certain it would sell to horn players, and called Clyde McCoy to

license it as the Vox Clyde McCoy Wah-Wah Pedal. The earliest versions boasted

McCoy’s likeness on the baseplate; later ones had just his signature.

Thomas Organ demonstrator/multi-instrumentalist Del Casher knew they had it

wrong. “This is really a guitar thing,” he told Benaron. In March of 1967, he

cut a demo 45 titled “Crybaby…” showing off the range of the wah from blues to

jazz, sitar to a tiger’s growl.

The Cry Baby moniker was used on the first Thomas Organ wahs. Listening to the

pedal scream, someone at Thomas said it sounded like a baby crying. The name

became famous.

Both the Cry Baby and Clyde McCoy – followed by Vox’s V846 successor – went into

production in early ’67, first in Sepulveda, then at Eko, in Italy. When Eko

balked at building the pedal, Benaron and Italian foreman Ennio Uncini launched

Jen (borrowing the first letters of their names) to make them. The pedals were

the same inside.

Thomas applied for a patent claiming first use of the “wow-wow sound” on June

27, 1967, and the patent was granted in 1970.